There are films that begin with a downward spiral into Eros in its most confrontational and lewd form. Images and sequences that sink, puncturing the surface of plot before rapidly plunging you deeper and deeper into a carnal pool until the light fades and the surrounding liquid becomes warm. There at the bottom you find yourself in complete darkness and silence. At these depths the pressure of the liquid presses darkness up against every orifice, waiting for a last, panicked spasm of breath or waning of muscle before invading the body. This process does not take very long. No film that plumbs these depths has ever been highly praised for patience or complexity of agenda. But while steeped in this liquid darkness, you might realise the mistake of writing off such efforts. You try to struggle and rationalize but it is too late. The picture is over. The sound has gone. You have drowned: this is the work of Walerian Borowczyk.

Borowczyk has made some of the most beautiful and curious films I have ever seen. His prolific output of complex and polemic work includes painting, sculpture, animation, live action film, documentary and television work.

Borowczyk began his career as a graphic designer and poster maker before moving into animation. His early animated short films made with the great Jan Lenica, such as “Byi Sobie Raz” (1957) and “Dom” (1958), are wonderfully energetic and exuberate a unique visual craftsmanship. In “Dom”, Włodzimierz Kotoński’s soundtrack pronounces a peculiar sense of humour in the excitable images, and it is this relationship that creates such a magical experience. Borowczyk embarked on a fruitful collaboration with composer Andrzej Markowski, beginning with the early short film “Szkola” (1958). In this film the combination of image and sound result in a haunting atmosphere; many of the images push my mind forward twenty-one years to the opening of Herzog’s “Woyzeck” (1979). But it was his short film collaboration with Chris Marker, “Les Astronautes” (1959) that formed a perfect marriage of idea, craft, humour and intent. The stunning use of movement, collage, and Markowski's sound, seem to create a floating dream world, a place where the director determines the gravitational field that boldly sends these elements crashing back down to earth.

His short films “Renaissance” (1963) and “Les Jeux des Anges” (1964) leave long lasting impressions and may be the most eerie works in his eclectic filmography. “Renaissance” is somewhat dedicated to the American photographer and experimental filmmaker Hy Hirsh. The film opens with a charred wall with fire-scorched debris all around. Suddenly the wallpaper begins to rematerialize, and unfurling from the soot it reappears in a brilliant white. A destroyed trumpet uncoils and reforms to its original condition, and then plays a tune. One by one, the burned and destroyed items pull themselves back together until the scene is pristine and untouched, only to explode again. On the other hand “Les Jeux des Anges” takes the viewer on a journey by train car through a maze-like subterranean world. The surreal forms and architecture wouldn’t seem out of place on a Max Ernst canvas; a city of small leaking chambers inhabited by amputated angel wings. These clambering subjects and manoeuvring images find some form of resolve in the ominous bed of sound created by Bernard Parmegiani. Overall, a strong presence of mortality and decay hangs over both of these films, and though there are bursts of vitality and movement the overshadowing sense of dread is not easily shaken off.

“Les Jeux des Anges” (1964)

His first feature film “Le Théâtre de Monsieur et Madame Kabal” (1967) is a startling piece of animation that really captures his humour, attention to detail, and surreal mapping of human desire. While subsequently moving into live action filmmaking, which later pressed deeper into the erotic, he continued to punctuate his career with many short gems throughout the late 1970s and 80s. His 1973 documentary short “Une collection particulière” is an exposition of erotic artefacts from novelist André Pieyre de Mandiargues’ private collection. The film is playfully intriguing and brandishes one of the greatest, most hilarious title sequences ever committed to celluloid. The title cards fade over what appears to be a magic lantern box consisting of a thin resin paper (screen) backlit and silhouetted by the maniacal coitus of a mechanical cartoon couple. Borowczyk made an alternative cut of the film, manoeuvring around the more explicit images, some even concerning bestiality, so that it would pass the board of censors. A longer uncensored 'Oberhausen-cut' of the film exists with differences in shot choices and duration, and does not include a voice-over.

Later, Borowczyk not only perused but also examined and detailed erotic fine art pieces in other short form documentaries such as “L’Escargot de venus” (1975) in which he explores some works by Bona Tibertelli de Pisis. The minimalistic documentary short “L’Amour monstre de tous les temps” (1977), briefly examines the great erotic painter Popovic Ljuba at work. In the film, a line or shape of paint seems chaotic and abstracted when isolated in close-up. Later these elements are revealed in having specific geometric importance in the shadow and form of the overall painting. In an effort to convey a blueprint of creative energy, brush strokes and other canvas work sit rhythmically between cutaway actions, re-contextualising the close-ups of painted shapes. The montage of this film is wonderfully constructive as the camera flows through some passing traffic, walking to the studio, the mixing of paint, the circling of the areola and formation of the nipple, to the washing of hands, and finally unveiling the completed work to the closing bombast of Wagner’s “Tannhäuser Overture”.

Borowczyk constructs a sense of distance and a smothering claustrophobia through the deconstruction of space. This is evident in his shooting through, and cross cutting rhythmically between, fast moving traffic. This was later tightened and brought to its full potential in “Cérémonie d’amour” (1987). In the latter film a chaotic scene unfolds when a man tries to ‘chat-up’ a woman with beautiful legs from an opposite platform of a busy train station. The end result is a quirky and unsettling scenario that seems to question the possibility of communication in contemporary society. One of his final animations from this period is “Scherzo Infernal” (1984), a rather humourous, though quite disturbing short set in the fiery pit of hell. Here it is possible to see the collision of various erotic ideas that were on the boil for some time, and their fusion with his unique brand of animation. The result is very memorable, in particular the red flickering flames that pulse the screen for most of the film.

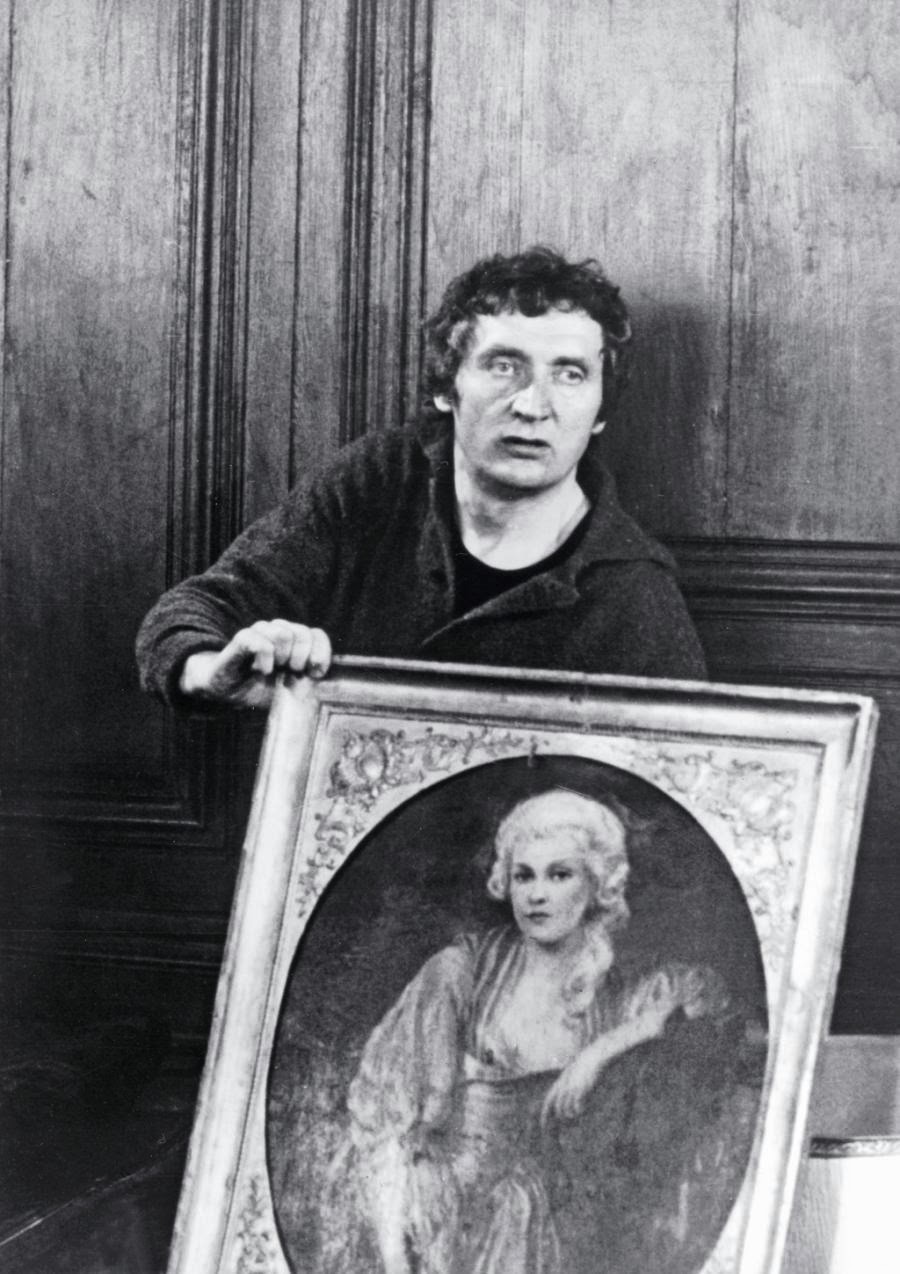

Ligia Branice in “Goto, l'ile d'Amour” (1968)

What is so interesting about Borowczyk is how he moved from delirious and abstract animation (often utilizing live action sequences) to fully live-action filmmaking with such certainty and attack. These early feature films, such as “Goto, l'ile d'Amour” (1968) and“Blanche” (1971) are particularly striking for their mise-en-scène and painterly qualities.

Borowczyk gave major roles to his wife Ligia Branice, who had appeared previously in his animations. Branice became a creative stimulus for these early films, appearing in “Dom”, “Les Astronautes” and “Rosalie” (1966) among others. She also cameos in Chris Marker’s “La Jetée” (1962). Marina Pierro, an actress discovered by Visconti in 1976, became Borowczyk’s latter day muse and starred in six of his films from 1978-90.

I have a particular fondness for films that bathe in the erotic and sensual misadventures of promiscuous characters. When following the joyous creatures in Pasolini’s “Trilogia della vita” (1971-1974), or the orchestrated whirling of ill-fated flesh in Jancso’s “Vizi privati, pubbliche virtù” (1976), I find myself presented with compounding, physical images. Another type of extreme physicality is present in the ratcheting fluidity of the female form in Zulawski’s cinema; a violent staccato that fires along like the plastic and tungsten emulsion through a projector, hurtling bodies and materials through lofts, passageways and streets. Oshima’s physical and emotional push of the human mind leads to the removal of the sex itself. In “Ai no korîda” (1977), castration is a means to an end or linking two people together forever. The film pushes the sensual into its darkest and reddest regions, as if to completely ‘take’ or alternatively, in a Makavejevian sense, make edible the human body.

“Contes immoraux”, (1974)

In Borowczyk’s world there is a feeling that anyone can engage with anyone (or anything) in any act, at any time. If something can happen, it certainly might happen. Perhaps this is an inheritance from working in animation. In his more erotic films, the potential for the ordinary to become sexual is constantly present, and the transformation of an everyday item into a masturbatory object is something that recurs. In “La Bête”(1975), after an interrupted sex session, the Marquis’ daughter relentlessly grinds her bedpost in an attempt to finish herself off. Elsewhere, prospective bride Lucy is frequently shown clasping a bed knob as she passes it by. Later in a fit of arousal she attempts to satisfy herself with it. In “Contes immoraux” (1974) it is a cucumber and it is a white rabbit in “Les héroïnes du mal” (1979). In “Le cas étrange de Dr. Jekyll et Miss Osbourne” (1981), when Jeykll transforms into Hyde his penis is transformed into a murder weapon. But it is “La Marge” (1976) that arguably presents us with the complete transformation of the body into an object. Here, the initially sterile detachment of sexual engagement with another body renders it inanimate.

In a way that is rather fantastical, “Interno di un convento ” (1978) hosts the transformation of another ordinary item. When a falling piece of log crashes through a convent window, a nun carves it into a phallus and commissions one of her friends to paint a portrait of her beloved on the base. Later, she pleasures herself with the object, keenly watching the portrait in a mirror, imagining that she is with her lover. This act was previously simulated in “Une collection particulière”, since a decorated wooden phallus and a small mirror box were among the artefacts documented.

In “Interno di un convento ” the close quarters of a secluded convent provide kindling for an orgiastic sexual awakening but the potential corruption of religious order, and a sexual love for Christ are themes that recur in other films. The second episode of “Contes immoraux” shows a young girl who has just returned from mass. While alone in her room she secretly reads from Jean-Baptiste de Boyer’s “Thérèse Philosophe”. She lies on her bed masturbating, draped in a sash she has stolen from the church. Her thoughts race back and forth to a private talk she had with the priest after the sermon. In these flashbacks she is seen in a trance-like state, stroking large, phallic ornaments. Later she goes to return the sash and while traveling across a beautiful field she is attacked and raped by a wandering tramp. The brisk presentation of this is very effective; a dark penance for erotic adventure.

“The Three Graces”, Raphael (1504-05)

“What about the composition? The rhythm?”

“If the painter cannot tell the tensor fasciae latae from the superior oblique, he dresses his model in a winter coat and covers her with tallow.”

“We also need prudish painters, alas.”

- Les héroïnes du mal, (1979)

There is a striking sense of rhythm and movement in Borowczyk’s films. His camera moves with jerky propulsion, lunging and spinning in short bursts, and in some scenes, changes perspective mid-sequence. In “Blanche”, upon the entrance of the King, the camera lumbers forward in medium shot first person, creating a sense of tension and uneasy propulsion. The rape/love scene in “La Bête” also contains one such interesting switch to first person. The camera rocks forward and backwards across the forest floor as the woman is penetrated from behind by the beast; the end result is disconcerting and nauseating.

His “Contes immoraux” not only features these fleeting point of view shots but also other examples of this montage technique. At the opening of the third tale, we are presented with a close up of Paloma Picasso’s eyes. She starts to open them- cut to birds exploding in flight -then back to linger on her eyes, now fully open. This arrangement is repeated again once the Countess sees the young girls washing themselves. We see a close up of her eyes that lingers briefly- a medium close up of girls washing parts of their bodies -then back to linger on her eyes. In “La Bête” we chase a young woman through the woods in a point of view shot from the beast’s perspective. Then we are given a reverse angle whereby she is running towards us. In this arrangement we are offered two experiences: a chance to condemn her, and a chance to save her. It is worth noting that steadicam legend Noël Véry was a frequent collaborator with Borowczyk, lensing “Contes immoraux”, “Escargot de Vénus” (1975), “L’Armoire” (1979), “Le cas étrange de Dr. Jekyll et Miss Osbourne” (1981) and “The Art of Love” (1983). Véry also acted as camera operator on many others including “Goto”, “Blanche”, “La Bête” and “La Marge”.

The result of Borowczyk’s camera switching between character viewpoint and the direct unveiling of an object or subject to the audience is interesting. Either way it could be a point-of-view similar to a groping act in passing, or one of completely meditated and ecstatic transfixion.

Another exhilarating piece of camera movement is seen in “Blanche” when Bartolomeo is hung, drawn and quartered. Horses drag him through the wilderness at high speed. The camera fires at trees, earth, sky, ditches, and rocky shapes of the apocalyptic landscape as it claws his body into a rag doll. The sound of horses galloping shrinks into echo as the camera riotously spins through sky and land. Then, abruptly, the image cuts to black and the film ends. Much like the ending of “Les Jeux des Anges”, a sound is isolated and intensified then abruptly cut, leaving the audience with silence and black screen. Borowczyk uses this trick better than most, and the final moments of “Blanche” are nothing short of devastating.

“Frenzy of Exultations” (Szał uniesień), Władysław Podkowiński, (1893)

In the cinema of Borowczyk innocence, its subversion, elimination and potentially destructive power are always (and most times quite literally) on the tip of the tongue. The disrobing of a young woman often cites a loss of innocence and whets the appetite for his camera (the assailant, lover). In nearly all of Borowczyk’s live action films (mostly period set) the women wear opaque gowns. When in direct light or soaked with water (which they often are) these ghostly veils become selectively transparent, rendering breast and pubic hair impressionistically visible. Complete nudity in itself could be considered saintly and pure, while these gowns, perhaps used to preserve those very things, present elements of the bodies selectively, encouraging the erotic which Borowczyk films like nobody else. Typically, once the gowns are removed, desires are fulfilled. However innocence is not so plainly portrayed. In the case of “Les héroïnes du mal”, once Margherita has deceived, robbed and murdered Raphael and Bini, she and her partner pour the stolen loot over her veiled breasts, massaging the golden ducats and jewels against her gown draped between her thighs. In this way the covering of clothes as a symbol of innocence is sometimes treated more ambiguously.

In “Blanche” a chain of murderous events is set in motion once the King and his page Bartolomeo set eyes on the vestal beauty of the title, because in a Sadean sense their monstrous lust had to reach some suitable end. It is also possible that Blanche’s innocent and chaste behavior is a contending factor in this undoing of her household, costing her life and the lives of her husband, potentially Oedipal son, and the spurned Bartolomeo. Similarly, the colour white is issued as a portent of purity, though simultaneously one of death and plague.

In Borowczyk’s early feature “Goto, l'ile d'Amour” he shows complete virtuosity in his use of tonal black and white. Movement is in the shape and texture as well as the structure of his frames: wonderful tableaux or panning and spectral explorations of female form. The white in “Goto” is the same as the all-encompassing light in “The Art of Love” or “Cérémonie d'amour”. Light comes from a pure place but is corrupted and already a ghost as it enters windows, moves though fabric, and curves naked bodies on the precipice of death before it reaches the screen.

Perhaps it is not so surprising that he took to colour in his live-action films with the same selective and at times sanguine intensity he brought to his animations. In Antonioni’s concocted letter to Samuel Goldman (“On Colour”, 1947) he says, “I think that Greta Garbo’s voice is violet, Barbra Stanwyck’s green. I think that Ingrid Bergman is a blue-pink young woman, and Lana Turner is brown….”. Transposing this to “Goto”, I can most certainly see colour in Borowczyk’s black and white, though here it smells of manure, soap and perfume, and tastes of copper with a texture of oily sand.

“Goto, l'ile d'Amour”, (1968)

Borowczyk utlises colour to incredible and painterly effect, particularly in his films from the early 1970s. His choice and combination of colours are very striking and immediately play on certain connotations. Perhaps reference could be made to Leon Battista Alberti, whose 1435 book “Della Pittura” expresses the importance of compartmentalizing colours, as well as their usage in combination and mixing, to introduce an infinite number of potential variations or hues. Alberti notes black and white as not being colours, and their usage desaturates and diminishes pure colour. A reading of white and black is present in “Les héroïnes du mal” when Margherita jealously insists that Raphael darken the hair of the woman in his fresco so that it will truly be in her likeness. He refuses, insisting that when at the correct distance and perspective, her hair will appear far darker. She later tells Raphael a nightmare of white death, where everything turned completely white including her family. Though a ploy to later tryst with the banker Bernardo Bini, the images of death are a foreshadowing for Raphael.

Red, Alberti’s ‘colour of fire’, is a favourite of Borowczyk. The poisonous red cherries on the cakes in “Les héroïnes du mal” posit the chance of death or love. While the red boots worn by Countess Báthory in “Contes immoreaux”, as she rides into town to procure young and beautiful women, and indeed the large room in which the girls are gathered, portend to the blood which she will later bathe in. Red here is seen as death and eternal life inextricably linked in the myth of Countess Dracula. In another simple gesture, the Marquis de l’Esperance in “La Bête” is seen standing in the crease of a dark, brown doorway, while behind him a deep, organ red corridor distends. He holds a terrible secret and will later commit murder. Once again, Borowczyk likes to play both cards simultaneously; the white semen of the beast brings life to a half-breed child, though the monster himself dies after copulation.

“Contes immoraux”, (1974)

“Les héroïnes du mal” displays a similar relationship with symbolism. The young Marceline is compared to a little lamb, only later to be raped in a pen of lambs ready for slaughter: a wonderful companion to Léaud’s character in Pasolini’s “Porcile”(1969), who copulates with pigs and is later devoured by them. Marceline’s rabbit “Pinky” (a feminine and ‘innocent’ colour like Lucy’s en-suite in “La Bête”) is killed and unwittingly fed to her in a stew by her horrible parents. Roaring with laughter they sing “our little stew smells very good!” Later, after the loss of her virginity, Marceline enacts revenge by leaving her rapist to hang and by slaughtering her parents with his knife. She then sits awake in an orphanage corrupting young girls with her tale.

Another rather obvious duality lies in a flower, for example the rose. In his Polish film “Dzieje grzechu” (1975), plucked rose petals decorate the body in a private and intimate ritual. Furthermore, in “La Bête” the rose is a pleasure-giving object to be devoured by the body, while in “Interno di un convento ” an encounter with the thorny roses of Christ’s crown results in ‘miraculous’ stigmata. The parallels of purification in beauty, death and sex flow like a bloody stream through Borowczyk’s work. These references are tremendous fun and his palette overflows with vibrant, renaissance symbols of passion and death, two things that are eternally entwined in his vision. In Borowczyk’s cinema, innocence bleeds.

“Contes immoraux”, (1974)

For an animator-come-filmmaker who meticulously created works from scratch, it is interesting to see the immediate influence of a wide variety of litereary sources. His reach extended from the Polish writers Juliusz Słowack and Stefan Żeromski to the more familiar Frank Wedekind, Guy de Maupassant, and Robert Louis Stevenson to Stendhal and the epic poet Ovid. There were also exciting plans for a Marquis de Sade adaptation in the 1980s which never materialized.

This love of history and the ‘personal history’ of literary characters seemed to endow his work with a specific sense of time and place, but ultimately it was his presentation of this time, and how he drew the characters within it, which marked his uniqueness as a live-action film director. His period work, though it evokes historical atmosphere and setting very faithfully, malingers in its own customized fantasy. In “Blanche” I feel a certain Bressonian quality in the faces of characters such as the aged Michel Simon. However, the presentation of ‘a specific period’ is closer to Pasolini than to the claustrophobic approaches adopted by Bresson or Dreyer. In “Le cas étrange de Dr. Jekyll et Miss Osbourne” we breathe a beautiful Victorian atmosphere, replete with furnishings of that era. Similarly “The Art of Love”, “Interno di un convento”, “La Bete”, “L’Armoire”, and “Lulu” (1980) are all works that have a specific historical context and Borowczyk enjoys revelling in the mysterious, dark and often floral recesses of the settings.

Having said that, one of Borowczyk’s most fascinating and mysterious images can be found in “Interno di un convento ”. A view from a high window shows a vast glistening body of water. This stunning Solaris-like image transcends any sense of time or setting, surrounding the convent in a mysterious ethereality that provides an exterior spiritual tension.

A body of water in “Interno di un convento”, (1978)

In contrast, the third tale from “Les héroïnes du mal”, “La Marge” and his final feature film “Cérémonie d’amour” are set in a recognizably modern, urban environment, which is arguably presented as confrontational.

This is especially so in “La Marge”, a tale of obsession, lust and deterioration in 1970s France. Based on André Pieyre de Mandiargues’ novel from 1967, this simultaneously unusual and conventional film follows a devoted family man, Sigismond (Joe Dallesandro), who goes on a business trip. While in the city he becomes obsessed with beautiful prostitute Diana (Sylvia Kristel), and during his trysts he is informed that his child has drowned and his wife has committed suicide. However, it is not long before all sense of time disappears as we are left with an abstracted series of detached, though beautifully photographed sex scenes that are sheathed in a pop soundtrack.

The contemporary setting is rather alarming at first, considering the drastic change from the usual Borowczyk universe. Kings, lutenists and all other elements of a period setting have been dispensed with. “La Marge” is a tale of love and obsession in a world of cafes, dive bars, brothels, gun-wielding pimps, dwarves, loaded jukeboxes, beautiful prostitutes, and of course it won’t end well for anyone. On paper the film intersects certain Fassbinder territories. Unfortunately even with all of these exciting ingredients it somehow fails to reach its true potential.

However, there is a sense of detachment that lingers on after viewing; allowing what should be a very mundane film to make its way under your skin. When Sigismond removes himself from family life and immerses himself in the carnal, we follow him. As he loses track of time and contact with his family, so do we. Later, he is informed that his wife and child (who we spent some time with at the beginning of the film) are both dead, and without much of a beat we spin deliriously further into this sordid world. While the basic plot and aesthetics are very conventional, the single-mindedness of the journey is not. It is a cold and calculated dive that gives little attention to anything beyond Sigismond’s obsession, and it is quite powerful for this reason. Though ultimately the film lacks the bite of his previous work, it is still a tough one to dismiss. “La Marge” is a film that improves with each subsequent viewing. The actors, setting, soundtrack, and overall impression make this a quintessential film of the 1970s.

Joe Dallesandro and Sylvia Kristel “La Marge” (1976)

It is a shame that in Borowczyk’s lifetime he never received the recognition that his uniquely adventurous filmography warranted. His live action films cover a lot of ground, and most of them reveal a very idiosyncratic framing of narrative. The best of these tales are fused with a feverish erotic delirium, and are justly courted with everything from the sounds of constructed instruments, diegetic chamber music, Hungarian folk, to Bach, and pop. Collaborations with composers Andrzej Markowski and Wlodzimierz Kotonski provided defining moments in his early film career, however the most intriguing sound works to feature in Borowczyk’s oeuvre are those by the renowned experimental composer Bernard Parmegiani. This most rewarding of relationships spanned several projects beginning with “Les Jeux des Anges” in 1964 and ending with “Scherzo Infernal” in 1984. One of the most unique of these collaborations, and perhaps the true culmination of their combined talents is “Le cas étrange de Dr. Jekyll et Miss Osbourne”. For this Parmegiani created a very disconcerting and chillingly erratic soundtrack by returning to elements of his work “Violostries” (1962).

Borowczyk’s later films have become a kind of folklore, his titles passed on by word of mouth and from tape to tape, some visible only as second generation VHS rips due to an overall sparse appearance on DVD. Alas, there was until recently very little widespread coverage and authenticated information on the filmmaker in circulation. This has slowly begun to change. In 2014 Arrow Films released a collector’s edition box-set of his films in the form of 2K scan BluRays complete with interviews and an extensive mini-book. The box-set was co-produced by Michael Brooke in conjunction with Ligia Borowczyk and the filmmaker’s assistant and producer, Dominique Segretin. This coincided with a retrospective of Borowczyk’s work at the BFI with events at the ICA over the summer. With “Le cas étrange de Dr. Jekyll et Miss Osbourne” set for release next year, I hope that more of his later works will follow so that I can finally see them as they were intended to be seen. Much of the praise for these Arrow restorations and the concomitant resurgence of interest is down to historian, writer and filmmaker Daniel Bird, who has been tirelessly championing Borowczyk’s work for nearly two decades.

“Walerian Borowczyk: The Listening Eye” at ICA, London, May 20 to July 6, 2014

Though a lot of his films could be seen as erotic, it would be crudely reductive to call them pornographic. Daniel Bird wrote of “La Bête”: …often described as an erotic film, La Bête is more of a Rabelaisian comedy. If anything it was a parody of pornography.”

Writer Tony McKibben addresses such concerns in his insightful essay “Perversions of Mise-en-Scène”. McKibben suggests that if we take Borowczyk as a pervert rather than a passive voyeur we are closer to the truth: “the voyeur is someone who accepts the material in front of him and who becomes excited by it, while the pervert wants to generate his own sexual world”. Indeed Borowcyzk generates just such an artisanal world of supreme beauty and erotic fantasy. He dares the viewer to leave their car keys in the dish and join a joyous orgy of murder, incest, corruption, betrayal, and bestial love. The further you wander in Borowcyk’s forest, the less likely you are to find your way back.

“A fistful of ashes and a few planks, nothing more”

Due to his dedication to ‘perverse’ beauty his most devout detractors find it very easy to spurn him for wasting his talent and slipping almost entirely into soft-core erotica. Initially, the basic case put forward by the oppugners might hold some weight; perhaps too much Borowczyk will make you go blind. But if a selection of his best work were among the last films you were to see, you would be haunted by their unique and powerful construction, abandon to avant-garde and sensual beauty, and titillated by their erotic expositions of love, madness and horror, which will reverberate in the darkness with you forever. At his best Borowczyk was one of the greatest filmmakers to emerge from post war Poland, and at his worst he was never boring.

In his obituary for the filmmaker, Ronald Bergan quoted Borowczyk saying:

"Film is a security valve for instincts that are condemned. The individual reveals himself outwardly, releases himself and hurts no one. He identifies with what he sees, kills via an intermediary and lives an experience through the cinema."

The cinema of Walerian Borowczyk is an experience indeed.

Some great articles with in-depth analysis of Borowczyk’s work can be read here:

- http://www.raymonddurgnat.com/publications_full_article_borowczyk_cartoon_renaissance.htm

- http://sensesofcinema.com/2005/feature-articles/borowczyk_heroines/

- http://sensesofcinema.com/2007/the-moral-of-the-auteur-theory/borowczyk-armoire/

- http://tonymckibbin.com/film/walerian-borowzcyk

- http://www.electricsheepmagazine.co.uk/features/2014/05/02/walerian-borowczyk-the-motion-demon/

- http://borowczykcollection.blogspot.ie/

- http://kinoteka.org.uk/daniel_bird.pdf

Words: Dean Kavanagh

Thanks to Maximilian Le Cain & Rouzbeh Rashidi